|

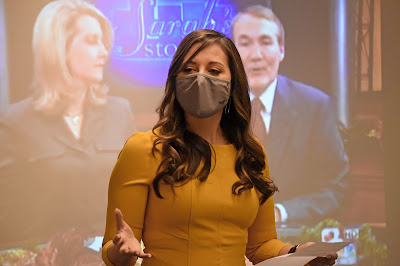

| Nicole Agee speaks March 22, 2022 in a Mount Mercy University journalism class. This image was made by a student in the class--images in this post are about half my work, half student work. |

The focus of good journalism shouldn’t be the journalist—an important point made by Nicole Agee, a local TV anchor (KCRG-TV Channel 9, Cedar Rapids, Iowa) in one of my classes.

“I’m not the story, the people I interview are the story,” she said.

Agee kindly volunteered to visit the class and talk about journalism storytelling, in particular, storytelling via video. As a sample, she showed a clip from KOMU, the Columbia, Missouri TV station associated with the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Journalism.

In video, the images and sounds are a key part of the reporting. Video in a story, Agee said, “takes the place of words.”

|

| Here and below, four more image of Nicole Agee speaking. |

It’s a large and complicated idea—it helps explain many of the differences between journalists who primarily work in words (we used to call it “print,” although these days, I read New York Times stories on a screen) vs those who are using video recordings. Agee also noted that radio, such as presented by NPR, is another medium with its own story telling style.

But whether words, video or audio, a journalist needs to be an accurate and compelling story teller.

Besides that, I think a beginning journalist needs to be ready to dive in—to get more experience however they can. Agee herself noted a history as a high school and college newspaper journalist before pursuing a graduate degree in broadcasting at Mizzou.

Agee also had some interesting thoughts on the skills needed to be a journalist. Primarily, she argued for the centrality of journalistic curiosity. “We want to know more, we want to know why,” Agee said.

In fact, she said it’s easier to work with a curious new journalist than with a new journalist who considers themself primarily a great writer. “It’s easy to train somebody to write well,” said.

Well, she’s wrong about that and right about it at the same time. A person has to have some base level language expression skills in order to be competent enough to be trainable as a writer. And I think curiosity is a driving force of most really good writers—to be a writer is not just to have facility with the language, it’s to have facility with ideas that can be expressed in language, which requires curiosity.

|

| Annie Barkalow, managing editor of the MMU Times, listens to Nicole Agee. |

But she’s right, too. Given a base level of writing competence, it’s easier to work on the information processing skills—whether writing, making images or shooting video—of a curious person. Students who struggle in one of my editing courses don’t always agree, but anybody can learn to create a page or web site using InDesign. What’s harder to teach is what should be on the page.

What’s required is the curiosity to seek new answers to common questions. Where do you go for information? What information is important for an audience you’re serving?

Curiosity may kill cats, but it is the life force of journalists.

So, although I work a lot at trying to teach writing—I think I’m fundamentally in agreement with Agee.

|

| Me, helping a student solve a problem with a camera. |

She made another key point, too. That is, a journalist must cultivate connections. She referred to building a personal Rolex when you arrive in a new community (while noting the term is outdated, today a network of contacts may be more related to a list on an Android phone than written cards that are quickly becoming antiques). In other words, a good journalist is active and aware and builds contacts before they must begin working on a given story.

I like to think of it as related to the role of imagination in journalism. That is, journalism, if done correctly, is not at all fiction. None of it is made up. But a journalist must be able to see possibilities, to sense patterns—not to impose narratives, to but recognize them and act on them. That’s related to the challenges of writing and editing, but also to the ability to think creatively when casting the net for information—for cultivating and well using a wide range of connections. An information, or source, network.

|

| I can't imagine what Nicole Agee was thinking about here, but whatever, it was worth listening to here. |

The class Agee visited was small—the smallest introduction to journalism class I’ve had in my time as a professor. Yet, as she noted, the skills one learns in a newsroom—working on deadline, being flexible, imaging the possibilities, acting on your curiosity—serve professionals in a variety of circumstances.

She was speaking of the many former journalists she knows who are working in other venues. I think it is one reason why college journalism remains important for a university. Of course, student journalists serve their community as journalists serve any community, by making overt what is hidden and should be known. But they serve themselves, too—developing habits of mind and skills that are keys to a curious, interesting, well-written life.

|

| Final image. |